When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you might wonder: Is this really the same as the brand-name drug you’ve been taking? It’s not just about cost. It’s about safety, effectiveness, and trust. The FDA doesn’t just approve generics because they’re cheaper. They require proof-rigorous, science-backed proof-that the generic works exactly like the original. That proof is called bioequivalence.

What Bioequivalence Really Means

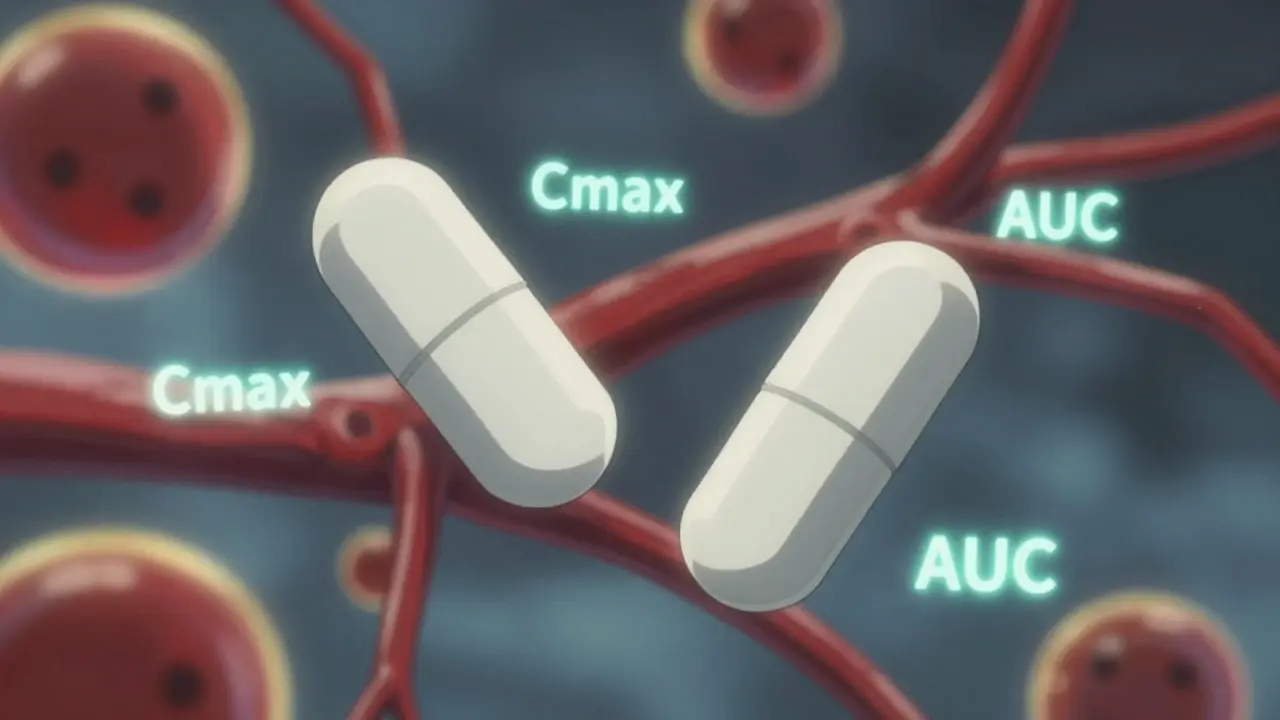

Bioequivalence isn’t about matching ingredients by weight. It’s not about matching color, shape, or even taste. It’s about matching how your body handles the drug. The FDA defines bioequivalence as the absence of a significant difference in the rate and extent to which the active ingredient becomes available at the site of action. In simple terms: if you take a generic drug, your body should absorb it and use it in the same way as the brand-name version.This isn’t guesswork. It’s measured. The FDA uses pharmacokinetic studies-tests that track how a drug moves through your body over time. Two key numbers are watched closely: Cmax (the highest concentration of the drug in your blood) and AUC (the total amount of drug your body is exposed to over time). These aren’t theoretical. They’re real, measurable values from blood samples taken from healthy volunteers after they take the drug.

The 80% to 125% Rule-What It Actually Means

You’ve probably heard the 80%-125% rule. But here’s the big misunderstanding: this doesn’t mean the generic can contain 80% to 125% of the active ingredient. That’s wrong. The active ingredient amount must be identical. The 80%-125% range applies to how your body absorbs the drug, not how much is in the pill.The FDA requires that the 90% confidence interval of the ratio between the generic and brand-name drug’s Cmax and AUC must fall entirely within 80% to 125%. Let’s say the brand-name drug gives an AUC of 100 units. The generic must show an AUC between 80 and 125 units-not just on average, but across the entire range of results from the study.

For example: if the generic’s average AUC is 93, but the 90% confidence interval stretches from 84 to 110, that’s approved. Why? Because 84 and 110 are both within 80-125. But if the average is 116, and the confidence interval goes from 103 to 130, it fails. Even though the average looks fine, the upper limit (130%) breaks the rule. The FDA doesn’t care about averages alone. They care about the full range of results. This ensures consistency across all patients, not just the average case.

How the Studies Work

Bioequivalence studies aren’t done on sick people. They’re done on healthy volunteers-usually between 24 and 36 people. Each person takes both the brand-name drug and the generic, in random order, with a washout period in between. Blood is drawn frequently over 24-72 hours, depending on the drug. The data is analyzed statistically to compare Cmax and AUC.These studies are expensive and tightly controlled. The FDA requires that they use the most accurate, sensitive, and reproducible methods available. That means labs must use validated assays, calibrated equipment, and strict protocols. No shortcuts. If a company runs a study that doesn’t meet FDA standards, it gets rejected-no matter how good the results look.

Pharmaceutical Equivalence Comes First

Before bioequivalence is even tested, the generic must be pharmaceutically equivalent. That means:- Same active ingredient

- Same strength

- Same dosage form (tablet, capsule, injection, etc.)

- Same route of administration (oral, topical, etc.)

- Same labeling (except for the name and manufacturer)

So if the brand-name drug is a 10mg extended-release tablet taken once daily, the generic must match that exactly. No changing the release mechanism to save money. No swapping out inactive ingredients that could affect absorption. The FDA checks this first. Only then do they move to bioequivalence testing.

What About Complex Drugs?

Not all drugs are the same. For drugs that work locally-like inhaled asthma meds or topical creams-the drug doesn’t need to enter your bloodstream. In those cases, the FDA may accept in vitro testing (lab tests on the drug’s physical properties) instead of blood tests.But for drugs meant to be absorbed into the blood-like antibiotics, blood pressure meds, or antidepressants-in vivo testing is required. The FDA has over 2,000 product-specific guidances to help manufacturers navigate this. For example, a generic version of a complex injectable or a nasal spray might need special testing protocols because their behavior in the body is harder to predict.

Why the FDA Changed the Rules

In 2021, the FDA started requiring companies to submit all bioequivalence studies they ran-not just the ones that worked. Before, companies could cherry-pick the best results. Now, if you ran five studies and only one passed, you still have to tell the FDA about the other four. This makes the approval process more transparent and reduces the chance of hidden problems.This change came after cases where generics were approved based on limited data, only to later show unexpected side effects or inconsistent performance. The FDA doesn’t want surprises. They want confidence.

Are There Exceptions?

Yes-for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index (NTI). These are medications where even a small change in blood level can cause serious harm. Think warfarin, lithium, or certain seizure drugs. For these, the FDA may require tighter bioequivalence limits, though they still use the standard 80-125% range as a baseline. Manufacturers of NTI drugs often run additional studies to prove consistency across batches and populations.Some experts argue the 80-125% range is too wide for these drugs. But the FDA maintains that, based on decades of real-world data, the range still works. They’ve reviewed thousands of cases and found no meaningful difference in clinical outcomes between brand-name and generic NTI drugs when bioequivalence is met.

The Bigger Picture

Generic drugs make up about 90% of prescriptions in the U.S. But they cost only about 20% of what brand-name drugs do. Over the last decade, generics saved the U.S. healthcare system nearly $2 trillion. That’s not just money-it’s access. Without bioequivalence standards, generic drugs wouldn’t be trusted. Doctors wouldn’t prescribe them. Patients wouldn’t take them.The FDA’s system works because it’s based on science, not assumptions. It’s not perfect, but it’s transparent, consistent, and constantly improving. The agency is now exploring modeling and simulation tools to reduce the need for human studies in some cases. That could speed up approvals for complex generics without lowering standards.

Bottom line: when you take a generic, you’re not taking a cheaper version. You’re taking a drug that’s been proven to behave exactly like the brand-name version in your body. The FDA didn’t just say so. They tested it. Repeatedly. And they’re still watching.

Do generic drugs have the same active ingredient as brand-name drugs?

Yes. Generic drugs must contain the same active ingredient, in the same strength and dosage form, as the brand-name drug. The FDA requires pharmaceutical equivalence before even testing for bioequivalence.

Can a generic drug be less effective than the brand-name version?

No-not if it’s FDA-approved. The bioequivalence requirement ensures that the rate and extent of absorption are the same. Thousands of studies and decades of real-world use confirm that FDA-approved generics perform the same as brand-name drugs in patients.

Why do some people say generics don’t work for them?

Sometimes, it’s not the drug-it’s the inactive ingredients. Different fillers or coatings can affect how fast a pill dissolves, which might cause minor differences in how quickly you feel effects. But this doesn’t change overall effectiveness. If you notice a change, talk to your doctor or pharmacist. Switching back to the brand or trying a different generic can help.

How long does it take for the FDA to approve a generic drug?

The standard review time for an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) is 10 to 12 months. About 65% of applications get approved on the first try. Many delays happen because of incomplete bioequivalence data or formulation issues-not because the drug doesn’t work.

Are all generic drugs tested on humans?

For drugs that need to be absorbed into the bloodstream, yes. In vivo bioequivalence studies with healthy volunteers are required. For drugs that work locally-like topical creams or inhalers-the FDA may accept lab-based (in vitro) testing instead.

Is the 80%-125% rule the same worldwide?

Most major regulators, including the European Medicines Agency and Health Canada, use the same 80%-125% range for bioequivalence. Some countries may adjust it for narrow therapeutic index drugs, but the FDA’s standard is widely accepted as the global benchmark.

Comments

Dan Mack January 14, 2026 AT 22:44

They say generics are the same but I've seen people crash after switching. The FDA doesn't test for long term effects. They just run a few blood tests on healthy kids and call it a day. You think they care about your kidney failing in 5 years? Nah. They care about saving a buck.

Amy Vickberg January 15, 2026 AT 21:40

I appreciate how thorough this breakdown is. It's easy to fear what you don't understand, but seeing the science behind bioequivalence really helps. Generics saved my family thousands last year and I'm glad the system works this way.

Crystel Ann January 17, 2026 AT 08:01

I used to be skeptical too. Then my dad switched from brand-name blood pressure med to generic and his numbers stayed perfect for 3 years. I guess the science really does hold up.

Jan Hess January 18, 2026 AT 19:23

This is why I trust generics. No fluff. Just hard data. The 80-125 rule sounds wild until you see how it protects patients. Real science beats marketing any day

Annie Choi January 20, 2026 AT 11:30

The pharmacokinetic parameters are non-negotiable in regulatory science. Cmax and AUC90% CI within 80-125% is the gold standard globally. Any deviation undermines statistical power and clinical predictability. The FDA's framework is robust.

Mike Berrange January 20, 2026 AT 23:43

You missed the part where the same company owns both the brand and generic. You think that's a coincidence? The FDA is a revolving door. Big Pharma writes the rules. You're being played.

Nishant Garg January 21, 2026 AT 14:02

In India we call this 'copy medicine'. But here's the thing - if it works in the lab and in the blood, why argue? My uncle took generic insulin for 10 years. Same HbA1c. Same life. No drama. Science doesn't care where you're from.

Sohan Jindal January 22, 2026 AT 11:31

America made the best drugs. Now we let foreign labs make knockoffs and call it progress. The FDA lets them get away with it because they're too busy kissing up to globalists. Our health is a commodity now

Frank Geurts January 23, 2026 AT 04:12

It is imperative to underscore the rigorous, methodologically sound protocols that underpin bioequivalence assessments. The statistical frameworks employed, including the 90% confidence interval, are not arbitrary; they are derived from decades of pharmacokinetic research and validated through international consensus.

Arjun Seth January 24, 2026 AT 03:25

People don't get it. Life isn't about numbers. It's about soul. You take a pill made in a factory in China with chemicals you can't pronounce and call it equal? That's not science. That's surrender.

Ayush Pareek January 25, 2026 AT 02:52

If you're worried about generics, start with your pharmacist. They can tell you which ones have the best track record. I've helped a lot of folks switch safely. It's not about fear - it's about knowing what to look for.

Iona Jane January 26, 2026 AT 01:46

I read about a woman who had a stroke after switching. They buried the report. The FDA has a list of 'silent failures'. You think they'll tell you? They don't even track long-term outcomes. It's all smoke and mirrors.

Jaspreet Kaur Chana January 26, 2026 AT 05:27

Bro I used to think generics were fake till I got my first one for my anxiety med. Same effect. Same sleep. Same calm. My wallet thanked me. Why overpay when the science says it's the same? Stop overthinking and save your cash

Haley Graves January 27, 2026 AT 20:44

The 80-125% range is fine for most drugs. But for NTI drugs like lithium, it's a gamble. I've seen patients destabilize. The FDA needs tighter limits - not more paperwork. Real safety means real limits.