Waking up to a blood sugar reading of 180, 200, or even higher-after eating well the night before and taking your meds-is one of the most frustrating experiences for people with diabetes. You didn’t overdo it on carbs. You didn’t skip your insulin. So why is your glucose sky-high in the morning? The culprit isn’t poor discipline. It’s likely the dawn phenomenon.

What Exactly Is the Dawn Phenomenon?

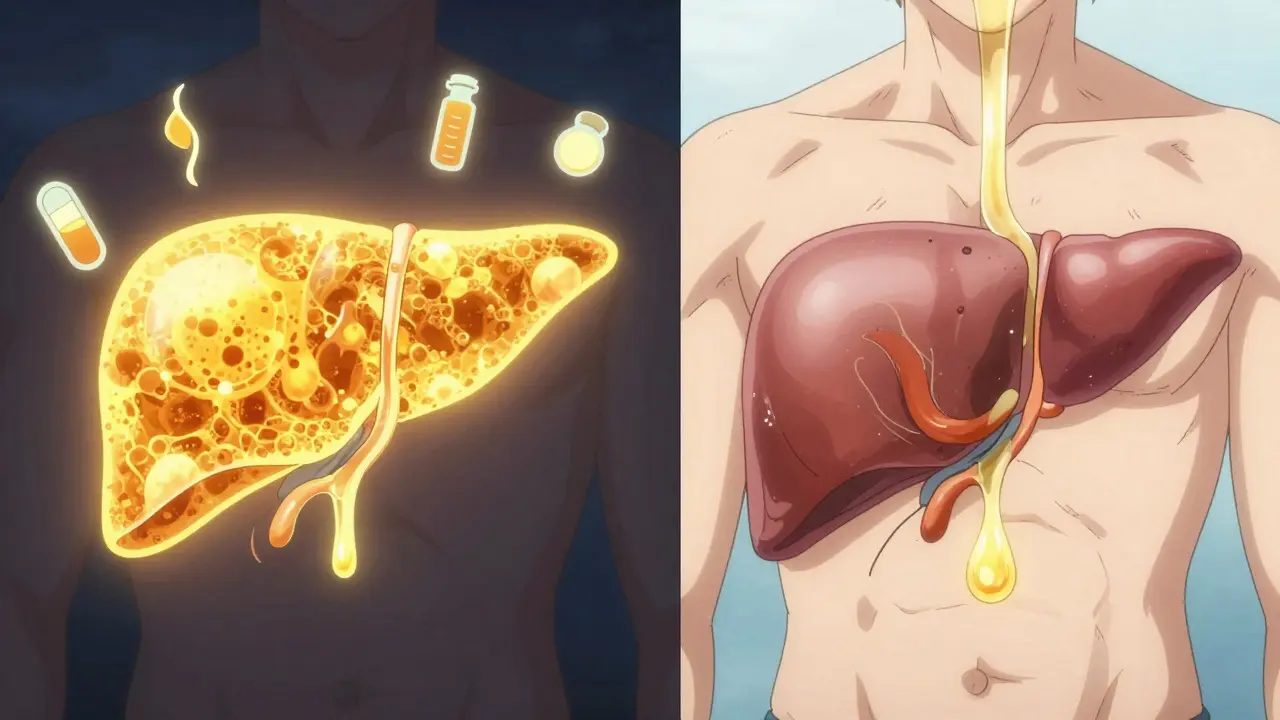

The dawn phenomenon isn’t a mistake. It’s biology. Between 3 a.m. and 8 a.m., your body naturally starts preparing for the day. Hormones like cortisol, growth hormone, and glucagon kick in. They tell your liver to release stored glucose into your bloodstream. In someone without diabetes, the pancreas responds by releasing just enough insulin to keep things balanced. But if you have Type 1 or advanced Type 2 diabetes, your body either doesn’t make insulin or can’t use it well. So that extra glucose piles up. By the time you wake up, your blood sugar can be 50 to 100 mg/dL higher than it was at bedtime.

This isn’t rare. About half of all people with Type 1 diabetes and half of those with Type 2 experience it regularly. Studies show it affects kids, adults, and seniors equally. A 2021 study in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism found liver glucose output jumps 20-30% during these early hours. For someone with diabetes, that’s enough to push morning levels into the danger zone.

Dawn Phenomenon vs. Somogyi Effect: Don’t Mix Them Up

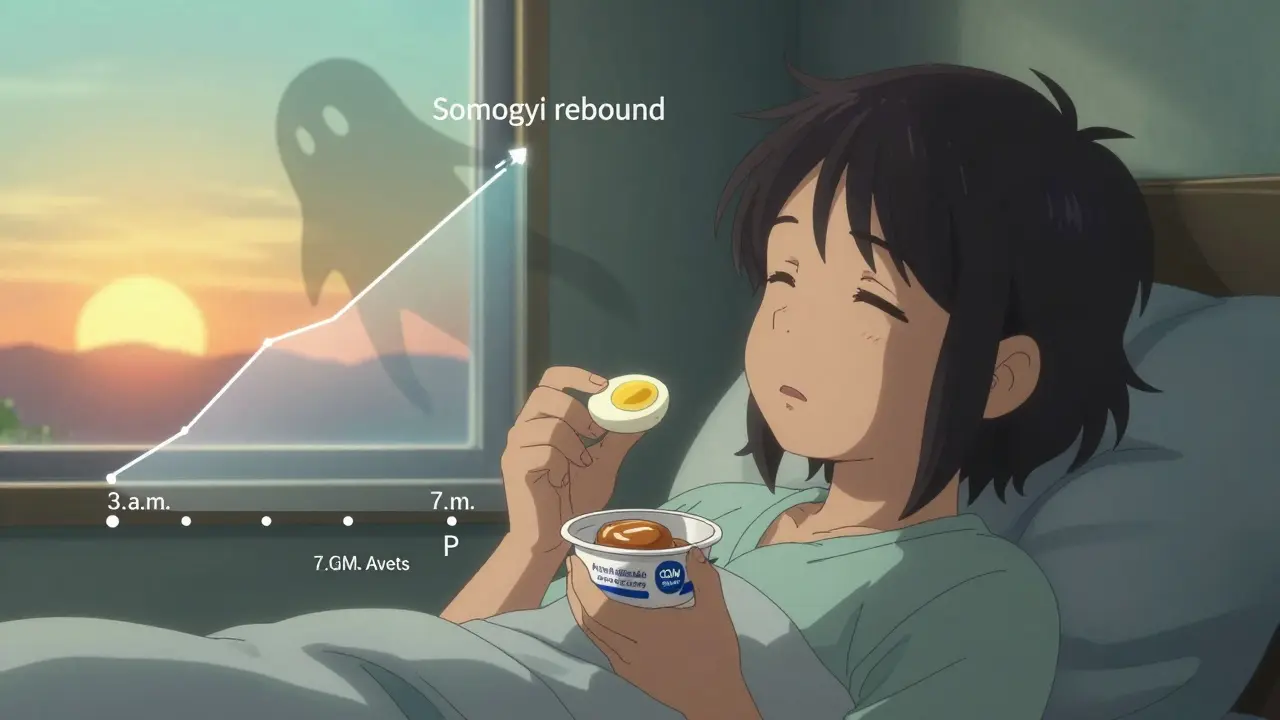

Many people confuse the dawn phenomenon with the Somogyi effect. But they’re completely different. The Somogyi effect happens when your blood sugar drops too low overnight (below 70 mg/dL), triggering a stress response. Your body releases hormones to rescue you, and in the process, it overcorrects-leaving you with high glucose in the morning. It’s a rebound.

The dawn phenomenon? No low blood sugar at all. Just a steady, natural rise starting around 3 a.m. with no dip. The only way to tell them apart? Check your glucose at 3 a.m. for three nights in a row. If it’s below 70 mg/dL, it’s Somogyi. If it’s above 100 mg/dL and climbing, it’s dawn phenomenon. Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) make this easy. Trend arrows showing a steady upward slope from 3 a.m. onward are the clearest sign.

According to Medtronic’s analysis of 10,000 CGM records, 68% of morning highs were due to the dawn phenomenon. Only 22% were Somogyi. Mistaking one for the other can make things worse. If you think it’s Somogyi and start eating more carbs at night, you’ll make the dawn phenomenon even worse.

Why It Matters: More Than Just a High Number

That morning spike isn’t just annoying. It adds up. Each 1% increase in your HbA1c raises your risk of complications-like nerve damage, kidney issues, or vision loss-by 21%. A 2023 study in Diabetes Care found that uncontrolled dawn phenomenon can raise HbA1c by 0.5 to 1.2 percentage points. That’s the difference between an HbA1c of 7.0% and 8.2%. One is manageable. The other is a red flag.

And it’s not just numbers. People report extreme thirst, fatigue, blurry vision, and frequent urination right when they wake up. For some, it triggers anxiety before they even get out of bed. A 2022 survey found 57% of people with diabetes felt the dawn phenomenon hurt their quality of life. One person on Reddit said, “I dread checking my glucose in the morning. It sets the tone for the whole day.”

How to Manage It: Practical Steps That Work

There’s no one-size-fits-all fix. But here’s what actually helps, based on real data and clinical trials.

1. Use a CGM

If you’re not using a continuous glucose monitor, you’re flying blind. CGMs show you the pattern-not just one number at wake-up, but how your glucose moves overnight. Dexcom G7, Abbott Libre 3, and Medtronic Guardian 4 all track trends. Look for that steady upward arrow from 3 a.m. to 7 a.m. That’s your signature. Without this data, you’re guessing. And guessing leads to dangerous adjustments.

2. Adjust Your Insulin (If You Use It)

For Type 1 users on insulin pumps or multiple daily injections, shifting your basal insulin rate is the most effective fix. The T1D Exchange Registry found that 62% of people who adjusted their nighttime basal rate lowered morning glucose by 45-60 mg/dL. Most increase their rate by 20-30% between 3 a.m. and 7 a.m. If you’re on an automated insulin delivery system like Control-IQ, newer versions now start adjusting as early as 2 a.m. to prevent the spike before it happens. Clinical trials show these systems cut morning highs by 58%.

For Type 2 users on insulin, talk to your doctor about switching your long-acting insulin to bedtime instead of dinnertime. Timing matters. A 2022 study found this simple change lowered morning glucose by 18-22 mg/dL.

3. Change Your Dinner

Carbs at night = fuel for the morning spike. The Joslin Diabetes Center found that limiting evening carbs to under 45 grams reduced morning glucose by 27%. That doesn’t mean no carbs. It means no pasta, rice, bread, or sugary desserts after dinner. Swap them for protein and healthy fats: grilled chicken, salmon, eggs, avocado, nuts, or a small portion of Greek yogurt.

A bedtime snack can actually help-if it’s the right kind. A small snack with 15g protein and 5g fat (like a hard-boiled egg with a tablespoon of almond butter) has been shown to stabilize glucose overnight. No sugar. No starch. Just slow-burning fuel.

4. Sleep Better

Poor sleep isn’t just tiring. It raises morning glucose by 15-20 mg/dL. A 2022 review in Sleep Medicine Reviews linked short or disrupted sleep to higher cortisol levels at night. Aim for 7-8 hours. Keep a consistent bedtime. Avoid screens an hour before bed. If you have sleep apnea, get it checked-it’s common in people with Type 2 diabetes and makes the dawn phenomenon worse.

5. Consider Newer Medications

For Type 2 diabetes, GLP-1 receptor agonists (like semaglutide or dulaglutide) are powerful. Taking them at night instead of in the morning helps suppress liver glucose production during the dawn window. The DURATION-8 trial showed this timing cut morning glucose by 18-22 mg/dL. New insulin formulations like once-weekly icodec (from Novo Nordisk) also show 28% better morning control than daily insulins.

What Doesn’t Work

Don’t just crank up your insulin dose at bedtime. That might cause low blood sugar overnight-and trigger the Somogyi effect. Don’t skip dinner to “avoid” the spike. That can make things worse by destabilizing your metabolism. And don’t assume your doctor knows what’s happening. Many still rely on fingerstick morning readings alone. Ask for a CGM report. Bring data. Be specific.

Real Stories: What People Are Doing

On diabetes forums, users report real wins. One woman with Type 1 switched from a 10 p.m. basal insulin to a 12 a.m. dose and cut her morning glucose from 210 to 130. Another started eating a small turkey and cheese roll-up at 9:30 p.m. and saw fewer spikes. A teenager with Type 1 used his CGM’s predictive alert to wake up at 3:30 a.m. and give a tiny correction bolus-cutting his morning highs by 70%.

But not everyone succeeds. Some users report increased nighttime lows after adjusting insulin. That’s why you need to monitor. Test at 3 a.m. before changing anything. Work slowly. Give each change 4-6 weeks to show results.

When to See Your Doctor

If you’ve tried dietary changes, sleep fixes, and insulin timing-and your morning glucose is still over 180 mg/dL on most days-it’s time to talk. Your provider may suggest:

- Switching insulin types or timing

- Adding a GLP-1 medication

- Starting or upgrading to an automated insulin delivery system

- Checking for other issues like sleep apnea or thyroid problems

Remember: the dawn phenomenon isn’t your fault. It’s a biological reality that only becomes a problem because of diabetes. The goal isn’t to eliminate it entirely-it’s to manage it so it doesn’t control you.

Is the dawn phenomenon the same as the Somogyi effect?

No. The dawn phenomenon is a natural hormone-driven rise in blood sugar between 3 a.m. and 8 a.m., with no preceding low. The Somogyi effect is a rebound high caused by an overnight low (below 70 mg/dL). The only way to tell them apart is to check your glucose at 3 a.m. for three nights. If it’s low, it’s Somogyi. If it’s high and rising, it’s dawn phenomenon.

Can I manage the dawn phenomenon without changing my insulin?

Yes, sometimes. Lifestyle changes like reducing evening carbs, eating a protein-rich bedtime snack, and improving sleep can lower morning glucose by 20-30%. For some people with Type 2 diabetes, switching GLP-1 medications to nighttime dosing helps. But if your morning levels stay above 180 mg/dL, insulin adjustments are often needed.

Do I need a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) to manage the dawn phenomenon?

You don’t absolutely need one, but you’ll struggle without it. Fingerstick checks only show you the result at wake-up. A CGM shows you the pattern-when it starts rising, how fast, and if you had a low earlier. Studies show 68% of new CGM users gain better control within three months. Endocrinologists now consider CGM essential for accurate diagnosis.

Why does my glucose spike even when I don’t eat carbs at night?

Your liver releases stored glucose during the early morning hours, regardless of what you ate. In people without diabetes, insulin stops this. But if you have diabetes, your body can’t respond properly. That’s why you get a spike even after a low-carb dinner. It’s not about food-it’s about insulin deficiency or resistance.

Can the dawn phenomenon lead to diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA)?

Yes, especially in Type 1 diabetes. If morning glucose stays above 250 mg/dL for hours without enough insulin, your body starts breaking down fat for energy, producing ketones. A 2023 study found 3.2 cases of DKA per 100 Type 1 patients per year were linked to uncontrolled dawn phenomenon. That’s why checking ketones during prolonged high readings is critical.

Comments

Greg Scott February 22, 2026 AT 00:14

Been dealing with this for years. Switching my basal to kick in at 2 a.m. was a game-changer. My CGM shows a flatline now instead of that scary upward arrow. No more dread checking my glucose in the morning. Just peace.

Scott Dunne February 23, 2026 AT 19:50

It is quite astonishing how poorly managed diabetes is in the United States. The notion that a simple hormonal fluctuation requires technological intervention is symptomatic of a broader medical overcomplication crisis. One should simply eat less and sleep better. End of story.

Chris Beeley February 25, 2026 AT 03:59

Let me tell you, my journey with the dawn phenomenon was nothing short of a metaphysical odyssey. I was trapped in a cycle of biological determinism until I discovered that my liver was essentially staging a coup against my pancreas - a silent, nocturnal rebellion fueled by cortisol and glucagon. I started journaling my dreams, tracking moon phases, and eating only organic, wild-caught salmon at precisely 8:47 p.m. - and guess what? My glucose stabilized. It wasn't just science. It was soul work. The real cure? Radical self-awareness. Also, I now take berberine. It's like metformin's mystical cousin. You're welcome.

Benjamin Fox February 25, 2026 AT 12:19

bro i just started eating peanut butter before bed and my morning numbers are down like 60 points 😎 no cap 🤝

Nina Catherine February 25, 2026 AT 15:33

OMG YES I DID THIS TOO!! I switched my GLP-1 to nighttime and it was like a whole new life?? I used to wake up at 4am crying because my glucose was 220 😭 now it’s like 110 and I can actually enjoy my coffee without panicking. also i think i spelled something wrong lol

Taylor Mead February 27, 2026 AT 12:52

For anyone struggling - don’t give up. It took me 6 months of trial and error, but once I started using my CGM’s trend arrows, everything clicked. I didn’t need to overhaul my life. Just small tweaks. Sleep. Protein snack. Basal tweak. That’s it. You got this.

Amrit N February 28, 2026 AT 09:51

bro i had the same issue till i started eating egg and almond butter at night. now my sugar is chill. also try not to stress too much. stress makes it worse. namaste 🙏

Robert Shiu March 2, 2026 AT 08:03

I’ve been there. Waking up to 200+ was crushing my mental health. But I found a community that helped me adjust my insulin timing - and now I sleep through the night. You’re not alone. Reach out. Talk to your care team. Small changes add up. And hey - if you need someone to vent to, I’m here.

Arshdeep Singh March 2, 2026 AT 16:53

You think this is bad? Wait till you meet the real enemy - insulin resistance caused by corporate food labs. Big Pharma doesn’t want you to know that the dawn phenomenon is just a symptom of a broken system. Eat real food. Avoid processed carbs. Stop trusting doctors who get paid by insulin companies. I’ve been doing this for 12 years. My HbA1c is 5.1. I don’t take meds. I eat mushrooms and walk barefoot on grass at dawn. Science? Nah. Truth.

madison winter March 4, 2026 AT 12:23

Interesting. But have you considered that the dawn phenomenon might be a metaphor for capitalist alienation? The body, like the worker, is forced to produce excess glucose during hours of enforced rest. The liver is the proletariat. The cortisol, the overseer. And insulin? A failed social safety net. Your struggle isn’t biological - it’s structural.

Jeremy Williams March 4, 2026 AT 13:48

While I appreciate the clinical rigor of this analysis, I must respectfully note that the cultural context of diabetes management in the Global North often overlooks the psychosocial dimensions of nocturnal glucose dysregulation. In many African and Asian societies, the concept of a ‘morning spike’ is not pathologized but contextualized within circadian rhythms tied to communal waking patterns. A more holistic model may be warranted.

Ellen Spiers March 6, 2026 AT 03:29

The data presented is methodologically sound, yet the conflation of correlation with causation in the dietary recommendations is concerning. The assertion that reducing evening carbohydrates leads to a 27% reduction in morning glucose lacks multivariate control for confounders such as physical activity, sleep architecture, and baseline insulin sensitivity. Furthermore, the reliance on CGM trend arrows as diagnostic gold standard is premature without validation against gold-standard euglycemic clamps. This is not evidence-based medicine - it is anecdotal epidemiology dressed in technocratic garb.

aine power March 6, 2026 AT 08:23

Protein snack. That’s it.

Tommy Chapman March 8, 2026 AT 07:23

Everyone’s just overcomplicating this. You’re eating too many carbs. You’re lazy. You don’t want to wake up at 3 a.m. to test. That’s why you’re high. Just do the work. Stop blaming biology.

Irish Council March 9, 2026 AT 11:42

Did you know the dawn phenomenon is a government mind control tactic? They want you dependent on insulin so they can track you via CGMs. The 3 a.m. spike? That’s when the satellites ping your glucose. I stopped using mine. Now I check with a fingerstick. I’m free.