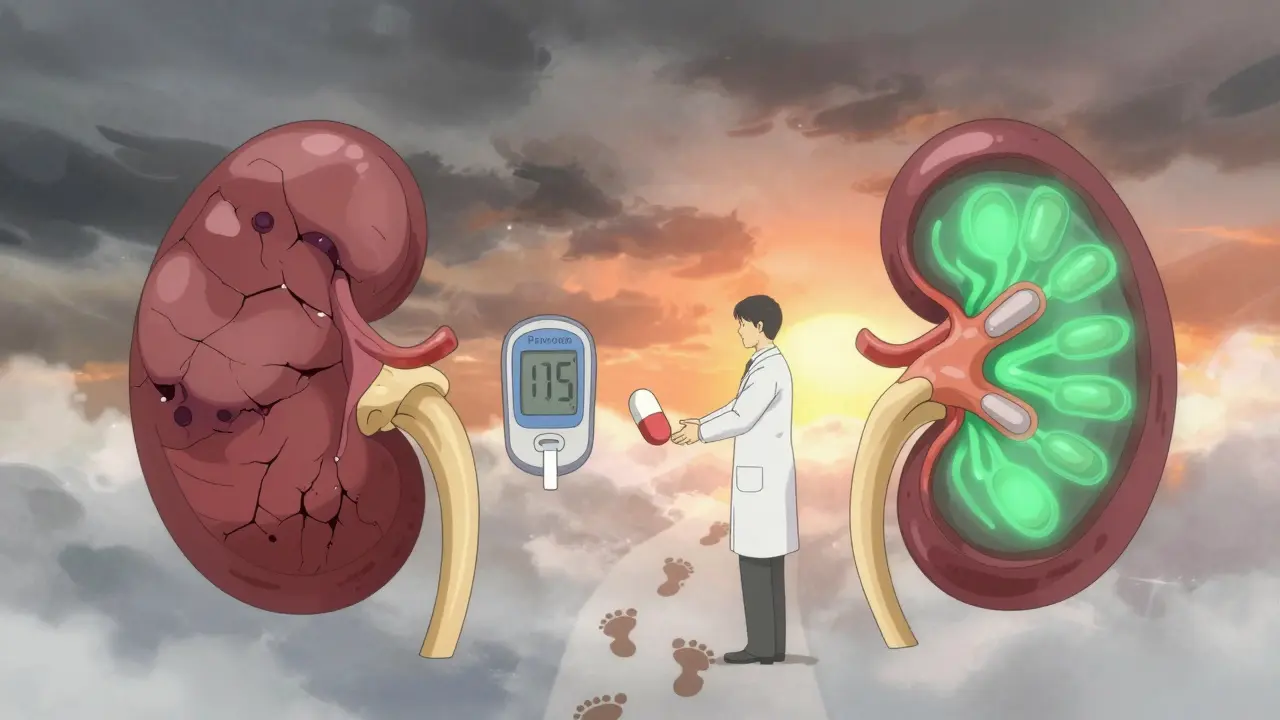

When your kidneys start leaking protein into your urine, it’s not just a lab result-it’s a warning sign your body is under siege. For people with diabetes, this leak is often the first and most telling sign of diabetic kidney disease (DKD). And here’s the hard truth: many don’t know it’s happening until it’s too late. But the good news? If caught early, you can stop it in its tracks. The key? Understanding albuminuria and acting fast with tight control.

What Is Albuminuria, and Why Does It Matter?

Albumin is a protein your kidneys normally keep in your blood. When they start to get damaged-usually from years of high blood sugar-they let albumin slip through into your urine. That’s albuminuria. It’s not a disease itself. It’s a signal. A very early one. The numbers matter. The Urine Albumin-to-Creatinine Ratio (UACR) measures how much albumin is leaking. Normal is under 30 mg/g. If it’s between 30 and 300 mg/g, that’s called moderately increased albuminuria. Above 300 mg/g? Severely increased. These aren’t just labels. They’re risk levels. A 2021 study of over 128,000 people with diabetes found that those with albuminuria over 300 mg/g had a 73% higher risk of dying from any cause-and an 81% higher risk of dying from heart problems-than those with normal levels. That’s not a small bump. That’s a red flag flashing on your dashboard.Why Screening Isn’t Optional-It’s Life-Saving

The American Diabetes Association says everyone with type 2 diabetes should get tested for albuminuria right at diagnosis. For type 1 diabetes, start testing after five years. And you need to do it every year. That’s not a suggestion. It’s a Class A recommendation-the highest level of evidence. But here’s the problem: in real life, only about 60% of clinics actually do this test regularly. Why? Lack of reminders in electronic records. Patients forgetting to collect urine samples. Doctors not knowing how critical it is. And it’s not as simple as one test. Albuminuria can spike temporarily from things like a bad cold, intense exercise, uncontrolled blood sugar, or even your period. So if one test shows high levels, you don’t panic. You repeat it. Two out of three abnormal results over 3 to 6 months? That’s when you know it’s real.Tight Glycemic Control: The Most Proven Shield

The most powerful tool to stop DKD before it starts? Keeping your blood sugar steady. The landmark DCCT study in the 1990s followed people with type 1 diabetes for decades. Those who kept their HbA1c under 7% cut their risk of early kidney damage by 39% and severe proteinuria by 54% compared to those with average HbA1c near 9%. The effect? It lasted. Even after the study ended, those who had tight control early on still had better kidney outcomes 20 years later. That’s called metabolic memory-your body remembers the damage you prevented. For type 2 diabetes, the UKPDS study showed something just as powerful: every 1% drop in HbA1c meant a 21% lower risk of developing kidney disease. That’s not linear. That’s exponential. Lowering your HbA1c from 8.5% to 7.5% doesn’t just help a little-it cuts your risk by nearly a quarter. Current guidelines say most people should aim for HbA1c under 7%. But if you’re young, have had diabetes for less than 10 years, and aren’t prone to low blood sugar, aiming for 6.5% can offer even more protection.

Blood Pressure: The Silent Partner in Kidney Damage

High blood pressure doesn’t just strain your heart. It crushes your kidneys. And in diabetes, the two go hand in hand. KDIGO guidelines say if your albuminuria is above 300 mg/g, you should aim for blood pressure under 120/80 mmHg. But here’s the catch: the SPRINT trial showed that pushing systolic pressure below 120 reduced albuminuria by 39%-but also increased the risk of sudden kidney injury in about 1 in 47 people. So the ADA recommends a more practical target for most: under 140/90 mmHg. That’s enough to protect your kidneys without risking harm. And if you’re on a blood pressure medication that blocks the renin-angiotensin system-like an ACE inhibitor or ARB-you don’t wait until your pressure is high to start. You start early. And you titrate it up to the highest approved dose, even if your pressure is normal. Why? Because these drugs protect your kidneys directly, not just by lowering pressure.The New Game Changers: SGLT2 Inhibitors and Finerenone

Glycemic control and blood pressure meds aren’t the whole story anymore. Two new classes of drugs have changed the game. First, SGLT2 inhibitors-like empagliflozin and dapagliflozin. The 2023 EMPA-KIDNEY trial showed that in people with DKD and UACR over 200 mg/g, taking empagliflozin cut the risk of kidney failure or death by 28%. It works by making your kidneys flush out sugar and salt, reducing pressure and inflammation inside the filtering units. Then there’s finerenone. This isn’t a typical steroid-based drug. It blocks a specific receptor in the kidney that causes scarring. In trials, it lowered albuminuria by 32% in just four months and slowed kidney function decline by 23% over three years-even in people already on maximum ACE/ARB therapy. These aren’t add-ons anymore. They’re now first-line. The 2024 ADA/KDIGO guidelines say: if you have DKD, you should be on an SGLT2 inhibitor. If you still have albuminuria above 30 mg/g after that, add finerenone.

The Gap Between Guidelines and Reality

Here’s where things get ugly. Even though we know all this, most people aren’t getting the care they need. NHANES data from 2017-2018 showed that only 12.2% of adults with diabetes hit all three targets: HbA1c under 7%, blood pressure under 140/90, and LDL cholesterol under 100. That means 88% are walking around with uncontrolled risk factors. And medication access? The CRIC study found only 28.7% of people with DKD are on all recommended therapies. Why? Cost. Lack of follow-up. Poor communication between specialists and primary care. And in low-income communities, it’s worse. But some clinics are fixing it. One hospital system started embedding UACR tracking into their electronic records. When a test came back abnormal, the system auto-sent alerts to the provider and scheduled a follow-up. Result? Follow-up rates jumped 37%. Another used point-of-care urine tests in the exam room-no need to take a sample home. That cut missed appointments by almost half.What You Can Do Today

If you have diabetes, here’s your action plan:- Get your UACR tested every year-no exceptions.

- If your result is above 30 mg/g, get two more tests over the next six months to confirm.

- Aim for HbA1c under 7%, or under 6.5% if your doctor says it’s safe.

- Keep your blood pressure under 140/90. If you’re on an ACE inhibitor or ARB, make sure you’re on the highest dose tolerated.

- Ask your doctor if an SGLT2 inhibitor or finerenone is right for you-even if your kidneys seem fine.

- Don’t ignore infections, stress, or high blood sugar. They can spike albuminuria and mask real damage.

What Happens If You Don’t Act?

Left unchecked, diabetic kidney disease doesn’t just fade away. It progresses. Albuminuria rises. Kidney function drops. Eventually, you need dialysis or a transplant. And even then, your risk of heart attack or stroke stays sky-high. But here’s the flip side: if you catch albuminuria early and act, you can reverse it. Some people with moderately increased albuminuria go back to normal levels with tight control. Others stabilize. Their kidneys stop deteriorating. Their lives get longer. Their quality of life stays better. The science is clear. The tools are here. The only thing missing is action.Can albuminuria be reversed?

Yes, in some cases. If caught early-especially in the moderately increased range (30-300 mg/g)-tight blood sugar control, blood pressure management, and medications like ACE inhibitors, SGLT2 inhibitors, or finerenone can reduce or even normalize albuminuria. Studies show up to 30% of patients with early DKD can see significant improvement or complete regression of albuminuria with consistent treatment.

How often should I get my urine tested for albuminuria?

Annual testing is recommended for all adults with type 2 diabetes at diagnosis and for those with type 1 diabetes after five years. Once albuminuria is confirmed, testing should be done every three to six months to monitor response to treatment. If levels stabilize and remain normal, annual testing is sufficient.

Can I test for albuminuria at home?

Home dipstick tests can detect large amounts of protein, but they’re not sensitive enough to catch early albuminuria. The UACR test requires a lab to measure the exact ratio of albumin to creatinine. Some clinics now offer point-of-care devices that give results in minutes during your visit, which improves follow-up rates. For accurate diagnosis and monitoring, lab testing is still the standard.

Do I need to stop eating protein if I have albuminuria?

No. High-protein diets don’t cause kidney damage in people with diabetes. In fact, cutting protein too low can lead to muscle loss and weakness, which worsens outcomes. Current guidelines don’t recommend protein restriction for DKD unless you’re in advanced kidney failure (eGFR below 30). Focus instead on controlling blood sugar, blood pressure, and taking proven medications.

Why are SGLT2 inhibitors recommended even if my blood sugar is under control?

SGLT2 inhibitors protect your kidneys independently of blood sugar control. They reduce pressure inside the kidney’s filtering units, decrease inflammation, and lower fat buildup in kidney cells. The EMPA-KIDNEY trial showed they reduce kidney failure and death even in people with normal or near-normal HbA1c. That’s why they’re now first-line for all diabetic kidney disease patients, regardless of glucose levels.

What if I can’t afford the new medications like finerenone or SGLT2 inhibitors?

Cost is a real barrier. But many pharmaceutical companies offer patient assistance programs. Generic ACE inhibitors and ARBs are still highly effective and affordable. Work with your doctor or pharmacist to explore options: co-pay cards, mail-order pharmacies, or state assistance programs. Even if you can’t get the newest drugs, controlling your blood sugar and blood pressure with existing meds still cuts your risk of kidney failure by more than half.

Comments

Allie Lehto January 25, 2026 AT 23:31

i just found out my uacr was 280 and i thought it was a typo 😭 i mean, i knew i was bad with sugar but this feels like the universe yelling at me. i started walking 10k steps a day and cutting out soda. not perfect, but i’m trying. 🙏

Henry Jenkins January 27, 2026 AT 01:22

The data here is solid, but what’s rarely discussed is the psychological toll of being told you’re failing your own body. It’s not just about HbA1c numbers-it’s about shame cycles, doctor’s office anxiety, and the guilt of ‘not trying hard enough.’ The medical system treats DKD like a math problem, but it’s lived in the body, in the silence between meals, in the fear of needles and tests. We need more compassion in the guidelines, not just more metrics.

John Wippler January 28, 2026 AT 03:24

Listen. I was diagnosed with type 2 in 2018. HbA1c was 9.8. I thought I had years. Turns out, I had months. My first UACR came back at 310. I cried in the parking lot. But here’s the thing-after 18 months of SGLT2, ARB, and zero sugar (yes, even in coffee), my albuminuria dropped to 22. Not just improved. Normal. It’s not magic. It’s discipline. And yeah, it sucks. But your kidneys don’t care about your excuses. They only care if you show up. So show up. For yourself. Today.

Kipper Pickens January 29, 2026 AT 14:08

Per KDIGO 2024, SGLT2i monotherapy is now Class I recommendation for DKD irrespective of glycemic status, with finerenone as adjunctive therapy for persistent albuminuria >30 mg/g despite SGLT2i. The mechanistic rationale lies in tubuloglomerular feedback modulation and NLRP3 inflammasome suppression. Cost-effectiveness models suggest incremental QALY gains of 0.83 over 10 years when initiated early, despite higher upfront pharmacoeconomic burden.

Aurelie L. January 30, 2026 AT 23:34

I’m just here to say… I’ve had diabetes for 22 years. My kidneys are fine. I don’t test. I don’t care. And I’m still alive. So maybe… you’re all overreacting?

Joanna Domżalska January 31, 2026 AT 05:54

So let me get this straight. You’re telling me if I just take pills and eat lettuce, my kidneys will magically heal? What about the 70% of people who can’t afford these drugs? Or the ones who live in food deserts? This isn’t medicine-it’s a guilt trip wrapped in a clinical trial. Stop blaming the patient. Fix the system.

Josh josh January 31, 2026 AT 20:44

uacr test is a joke. my doc said i had to pee in a cup and mail it. i forgot. then i did it wrong. then i was too stressed to do it again. now they say i have to wait 3 months. meanwhile my sugar is spiking and i’m just trying to survive. why does this have to be so hard?

Geoff Miskinis February 2, 2026 AT 06:13

The empirical rigor of the DCCT and UKPDS is admirable, yet the generalizability of these findings to populations with comorbid obesity, socioeconomic disadvantage, or non-Caucasian genetic backgrounds remains underexplored. One wonders whether the ‘tight control’ paradigm is merely a reflection of Western biomedical hegemony, rather than a universally applicable clinical imperative.

Betty Bomber February 3, 2026 AT 21:36

i took my first uacr test last week. it was 45. not bad, right? but i’ve been avoiding my doctor since then. like… what if they tell me i need to change everything? i’m not ready. but i’m scared to not be.

Shawn Raja February 5, 2026 AT 19:54

so we’ve got a 28% reduction in kidney failure with SGLT2i… but you’re telling me the average patient still doesn’t even get tested annually? That’s not a medical failure. That’s a societal comedy. We spend billions on fancy new drugs while people can’t get a $10 urine test. The real miracle drug? A functioning healthcare system. But hey, at least we’ve got finerenone. 🙃