Kidney Stone Risk Assessment Tool

Personal Risk Assessment

Key Takeaways

- Kidney stones come in five main compositions, each with distinct causes.

- Calcium‑based stones are the most common, but diet, infection and genetics matter.

- Laboratory analysis of the stone is the definitive way to identify its type.

- Tailored prevention - more water, specific dietary tweaks, or medication - cuts recurrence dramatically.

- Seek urgent care for severe pain, fever, or blood in the urine.

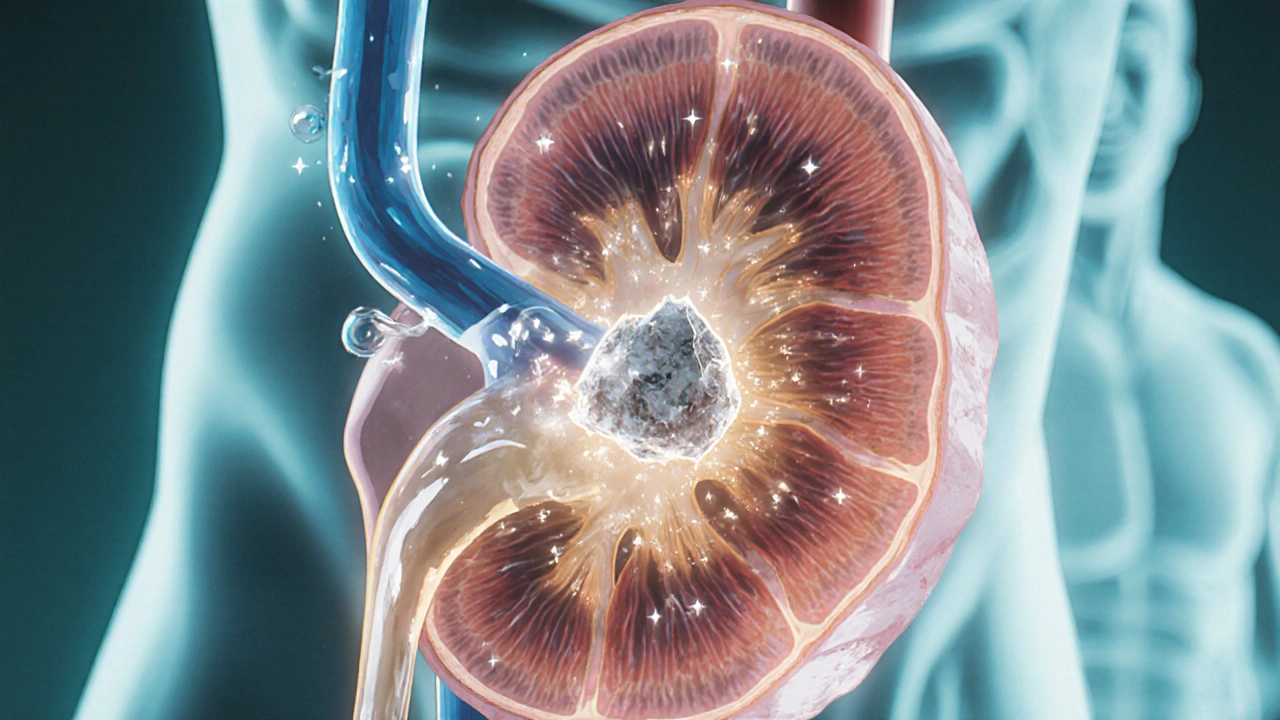

When a mineral crystal builds up in the urinary tract, a kidney stone is formed. Kidney stones affect roughly 1 in 10 people worldwide, and their pain can feel like the worst cramp you’ve ever endured. The good news? Knowing the stone’s composition lets you pick the right diet, fluids, and medication to keep new stones from forming.

How Kidney Stones Form

Every day your kidneys filter about 150liters of blood, extracting waste and excess minerals. Normally, these substances dissolve in urine and exit the body harmlessly. When urine becomes too concentrated, or when certain chemicals bind together, they can crystallise. Over time the crystals grow into stones that may lodge in the kidney, ureter, or bladder.

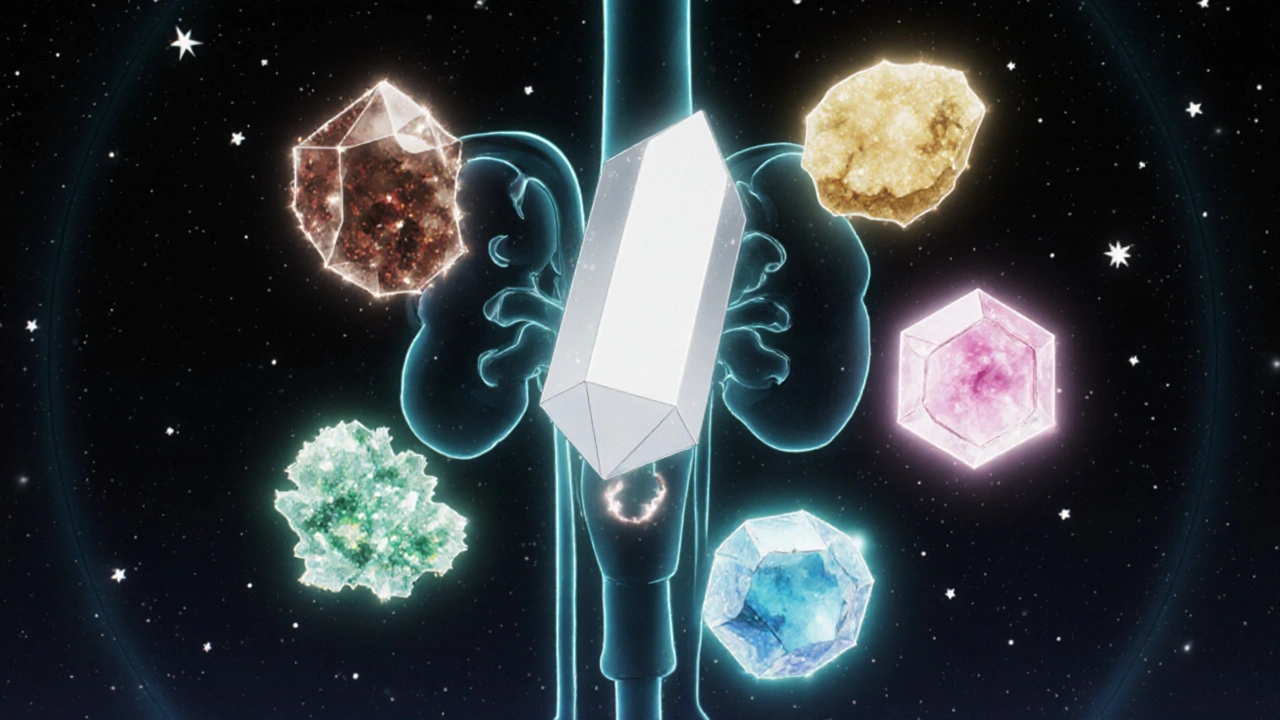

Major Types of Kidney Stones

Scientists classify stones by what they’re made of. Five types account for the overwhelming majority of cases:

Calcium Oxalate Stones

Calcium oxalate stone is the most prevalent, responsible for about 70‑80% of all stones. They form when calcium binds with oxalate, a natural waste product found in foods like spinach, nuts, and chocolate. High oxalate intake, low urine volume, and hypercalciuria (excess calcium in urine) all raise the risk.

Calcium Phosphate Stones

Calcium phosphate stone makes up roughly 10‑15% of cases. These stones usually appear in people with alkaline urine, certain metabolic disorders, or chronic urinary infections. Diets rich in dairy and certain supplements can increase phosphate levels.

Uric Acid Stones

Uric acid stone is the third most common type, especially in men and people with gout. High purine intake (red meat, organ meats, seafood) raises uric acid in the blood, which can precipitate when urine is acidic. Rapid weight loss and dehydration also contribute.

Struvite Stones (Magnesium Ammonium Phosphate)

Struvite stone, also called magnesium ammonium phosphate stone, forms rapidly after urinary tract infections with urease‑producing bacteria (e.g., Proteus). They can grow large, cause blockage, and sometimes form staghorn calculi that fill the kidney’s collecting system.

Cystine Stones

Cystine stone is rare, accounting for less than 1% of stones, and results from a hereditary defect called cystinuria. The kidneys leak cystine, a poorly soluble amino‑acid, into the urine, which then crystallises.

How to Identify the Stone Type

The only way to know a stone’s exact makeup is through analysis after it’s passed or removed. Here’s the typical workflow:

- Imaging: A non‑contrast CT scan shows stone size, location, and density (measured in Hounsfield units). Higher density often points to calcium‑based stones.

- Urine testing: 24‑hour urine collections reveal supersaturation of calcium, oxalate, uric acid, citrate, and other markers.

- Stone analysis: Infrared spectroscopy or X‑ray diffraction determines the precise mineral composition.

Armed with this data, your clinician can tailor preventive therapy.

Prevention Strategies Tailored to Each Stone Type

While all stone formers benefit from basic habits, fine‑tuning your approach to the stone’s chemistry yields the biggest payoff.

Calcium Oxalate

- Drink at least 2‑3L of water daily to keep urine volume>2L.

- Limit high‑oxalate foods (spinach, rhubarb, almonds) if you’re a frequent oxalate former.

- Consume dietary calcium (1g/day) with meals to bind oxalate in the gut, reducing absorption.

- Consider potassium citrate supplementation if urine citrate is low.

Calcium Phosphate

- Maintain urine pH between 5.5-6.5; avoid excessive alkali (bicarbonate) unless prescribed. \n

- Reduce sodium intake (<2g per day) because high sodium drives calcium excretion.

- Limit animal protein that can increase urinary phosphate.

Uric Acid

- Alkalinise urine with potassium citrate to keep pH>6.0, which solubilises uric acid.

- Cut purine‑rich foods (red meat, shellfish) and fructose‑sweetened beverages.

- Maintain a healthy weight; rapid dieting spikes uric acid.

Struvite

- Promptly treat urinary tract infections; a short course of culture‑directed antibiotics can prevent stone regrowth.

- Ensure regular bladder emptying; consider a low‑sodium diet to reduce urinary phosphate.

- In recurrent cases, a low‑dose urease inhibitor (e.g., acetohydroxamic acid) may be prescribed.

Cystine

- Increase fluid intake dramatically - aim for >4L/day to keep cystine concentration low.

- Alkalinise urine to pH7.5-8.0 with potassium citrate or bicarbonate.

- Thiols such as tiopronin can bind cystine, making it more soluble (used under specialist supervision).

When to Seek Medical Care

If you experience any of the following, call emergency services or your urologist immediately:

- Severe, colicky flank pain that radiates to the groin.

- Fever>38°C (100.4°F) or chills, indicating possible infection.

- Visible blood in the urine (gross haematuria).

- Persistent nausea, vomiting, or inability to pass urine.

Early intervention can relieve pain, prevent kidney damage, and avoid complications like sepsis.

Comparison of Kidney Stone Types

| Stone Type | Typical Composition | Common Risk Factors | Urine pH Trend | Prevention Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium Oxalate | Calcium + Oxalate | High oxalate diet, low urine volume, hypercalciuria | Neutral‑acidic (5.5‑6.5) | Hydration, dietary calcium with meals, limit oxalates, citrate |

| Calcium Phosphate | Calcium + Phosphate | Alkaline urine, hyperparathyroidism, high sodium | Alkaline (>6.5) | Reduce sodium, avoid excess alkali, maintain moderate calcium |

| Uric Acid | Uric acid crystals | Gout, high purine diet, obesity, acidic urine | Acidic (<5.5) | Alkalinise urine, cut purines, weight control |

| Struvite (Magnesium Ammonium Phosphate) | Magnesium, ammonium, phosphate | Recurrent UTIs with urease‑producing bacteria | Alkaline | Prompt infection treatment, possible low‑dose urease inhibitors |

| Cystine | Cystine (amino‑acid) | Cystinuria (genetic), low urine volume | Neutral‑alkaline (6.0‑7.5) | High fluid intake, urine alkalinisation, thiol therapy if needed |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most common type of kidney stone?

Calcium oxalate stones are by far the most common, responsible for about 70‑80% of all cases.

Can kidney stones be prevented without medication?

Yes. For most stone formers, drinking enough water, adjusting diet (e.g., limiting oxalates or purines), and maintaining a healthy weight can dramatically lower recurrence risk.

How long does it take for a stone to pass naturally?

Small stones (<4mm) often pass within a few days to two weeks. Larger stones may need medical intervention.

Is a low‑calcium diet recommended for kidney stones?

No. Restricting dietary calcium can increase oxalate absorption, worsening calcium‑oxalate stone risk. Instead, aim for normal calcium intake spread across meals.

What role does urine pH play in stone formation?

Urine pH determines which minerals stay dissolved. Acidic urine favours uric acid stones, while alkaline urine promotes calcium phosphate and struvite stones.

Comments

James Falcone October 17, 2025 AT 12:42

Listen, if you want to dodge kidney stones you gotta remember that the typical American fast‑food binge is a one‑way ticket to calcium overload. Load up on water, ditch the soda, and stop treating your kidneys like a trash can for junk. It’s not rocket science, just common sense for a country that claims it invented the diet‑hard‑drive.

Frank Diaz October 23, 2025 AT 07:35

Stone formation is, in essence, the body's silent protest against the chaos we feed it. When you ignore the subtle chemistry of your own fluids, you permit crystalline tyranny to take hold. One could argue that the real ailment lies not in the mineral but in the mind that refuses discipline.

Valerie Vanderghote October 29, 2025 AT 01:29

It is astonishing how often we approach health information as if it were a fleeting Instagram story, skimming the surface and never truly absorbing the depth of the science behind kidney stone formation. The cascade begins with a seemingly innocuous reduction in urine volume, a factor that could be as simple as neglecting to carry a reusable water bottle, yet it sets the stage for supersaturation of calcium and oxalate ions that ultimately coalesce into a painful concretion. Moreover, the dietary patterns ingrained in our culture-excessive consumption of processed foods, high sodium intake, and the casual indulgence in chocolate and spinach-serve as silent architects of these crystalline structures.

Each of these dietary choices influences the urinary pH, the availability of binding partners, and the renal handling of electrolytes, creating a perfect storm that predisposes susceptible individuals to stone genesis. The genetic predisposition, such as hypercalciuria, only amplifies the risk when paired with lifestyle factors, rendering the prevention puzzle a multifaceted challenge. Consequently, the recommendation to increase fluid intake to a minimum of two liters per day is not merely a banal suggestion but a cornerstone of diluting urinary solutes to sub‑crystallization thresholds.

In addition to hydration, the strategic timing of calcium consumption with meals acts as a chelating agent for oxalate, preventing its absorption and subsequent urinary excretion. This nuanced interplay between mineral balance and dietary timing underscores the importance of personalized nutrition strategies. The role of citrate, whether obtained through citrus fruits or pharmacologic supplementation, cannot be overstated, as it binds calcium and impedes crystal nucleation.

Furthermore, the distinction between stone types-calcium oxalate, calcium phosphate, uric acid, struvite, and cystine-demands a tailored approach that considers urine pH modulation, purine restriction, and, in rare hereditary conditions, advanced pharmacotherapy. Ignoring these subtleties amounts to a reckless gamble with one’s renal health. The comprehensive analysis of a passed stone, via infrared spectroscopy, provides the definitive blueprint for targeted prevention, making it an indispensable tool in clinical practice.

Ultimately, the amalgamation of diligent hydration, mindful dietary choices, and precise biochemical monitoring converges to create a robust defense against recurrent nephrolithiasis, transforming a potentially debilitating condition into a manageable, and often preventable, aspect of one’s life.

Michael Dalrymple November 3, 2025 AT 20:22

While the passion in earlier comments is commendable, let’s focus on actionable steps. Begin by tracking your daily fluid intake, aiming for at least 2.5 L of water per day, and consider a urine pH test strip to gauge acidity. Adjust your diet gradually-incorporate calcium‑rich foods with meals and reduce high‑oxalate items if you’re prone to calcium oxalate stones. Consistency, not intensity, will yield lasting protection.

Darryl Gates November 9, 2025 AT 15:15

Accurate stone analysis is the linchpin of a successful prevention plan. Laboratory infrared spectroscopy will delineate the exact mineral composition, allowing the clinician to prescribe targeted interventions. For calcium oxalate formers, maintaining a urine volume greater than two liters and supplementing with potassium citrate when citrate is low are evidence‑based measures. Patients should also be advised to limit sodium intake to under 2,300 mg per day to reduce calcium excretion.

Kevin Adams November 15, 2025 AT 10:09

Oh the tragedy!-a stone the size of a marble, a silent tyrant lurking in the renal pelvis! Why does our body betray us? Because we ignore the whispers of chemistry, the subtle dance of ions! Drink, eat, move-simple, yet we stand idle as pain erupts like a volcano!

Joanna Mensch November 21, 2025 AT 05:02

They don’t want you to know that the pharmaceutical industry pushes alkaline water as a cure while hoarding the real antidotes. Every “dietary recommendation” is a carefully placed nudge to keep you buying their supplements. Trust your own urine tests, not the glossy ads.

RJ Samuel November 26, 2025 AT 23:55

Honestly, I think all this stone talk is overblown-most people will never need a CT scan if they just stop chasing the latest health fad. The body’s natural mechanisms are far more resilient than these manuals admit, so maybe we’re just pathologizing normal variability.

Nickolas Mark Ewald December 2, 2025 AT 18:49

Stay hydrated and cut back on salty snacks.

Rebecca Mitchell December 8, 2025 AT 13:42

Drink water enough keep urine diluted you’ll avoid most stones its simple

Roberta Makaravage December 14, 2025 AT 08:35

As anyone who has consulted the latest urology guidelines will attest, stone composition dictates therapy 🤓. Calcium oxalate dominates, so your primary goal is to increase urine volume and ensure dietary calcium binds oxalate. Uric acid stones require alkalinization, often achieved with potassium citrate, and a low‑purine diet 🍋. Struvite stones are infection‑driven; definitive management includes prompt antibiotics and possibly stone removal. Cystine, though rare, demands aggressive hydration >4 L/day and thiol‑binding agents. Follow these evidence‑based protocols and you’ll dramatically slash recurrence rates 🚀.

Lauren Sproule December 20, 2025 AT 03:29

hey folks! just wanted to say that staying hydrated is key and dont forget to watch ur pH levels. also, cutting down on soda can really help ur kidneys. keep it up and u’ll feel better n’ healthier :)

CHIRAG AGARWAL December 25, 2025 AT 22:22

Honestly, reading this whole guide feels like a marathon of boring details. I get the gist-drink water, watch your diet-but the endless tables and jargon could be trimmed down to a quick cheat‑sheet.