When you’re first diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, the focus is often on the relapses - the sudden numbness, the blurred vision, the loss of balance. But what happens between those flare-ups? Why do some people keep getting worse, even when the flares stop? The truth is, multiple sclerosis isn’t just about inflammation. The real damage - the kind that changes your life permanently - happens quietly, over years, as nerves in your brain and spine slowly die.

What’s Actually Going Wrong in Your Nervous System?

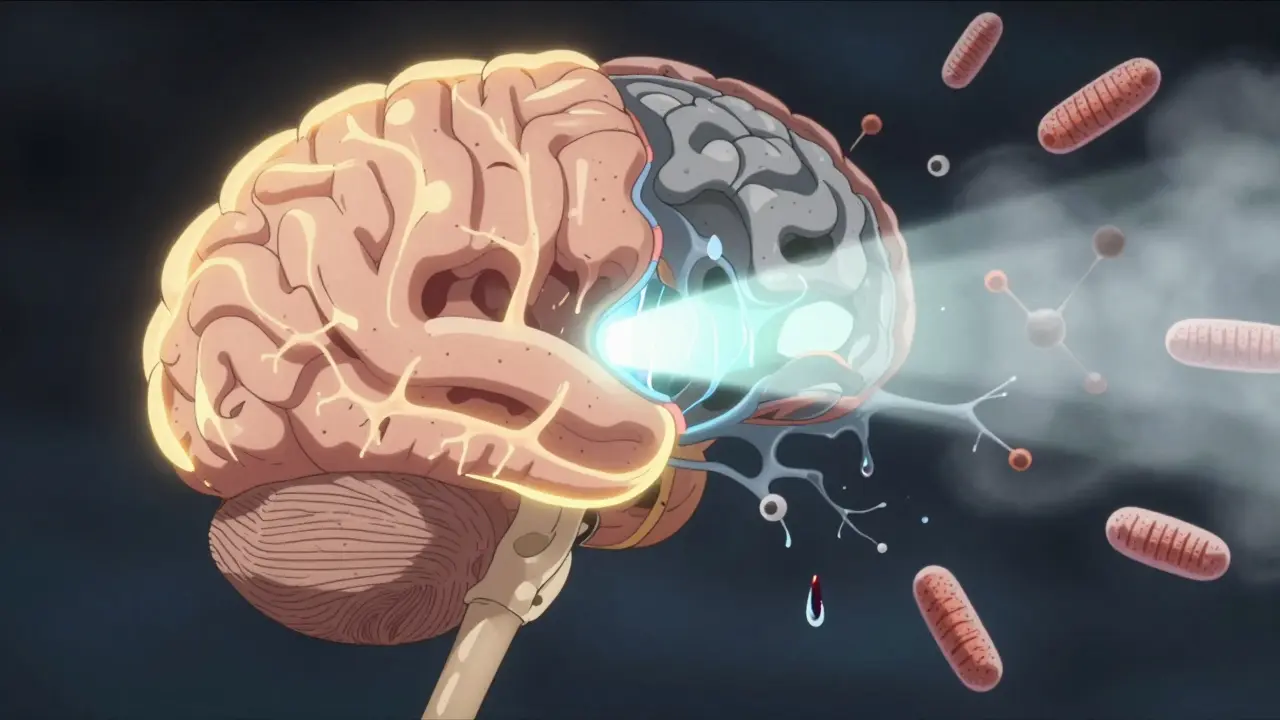

Multiple sclerosis attacks the myelin sheath - the fatty insulation around nerve fibers that lets electrical signals zoom through your body. Think of it like the plastic coating on an electrical wire. When that coating gets stripped away, the signal stutters or dies. That’s what causes the symptoms: weakness, tingling, trouble walking, even memory problems. But here’s the catch: your body can sometimes fix the myelin. In the early stages, especially in relapsing-remitting MS, your nervous system can repair itself. That’s why you might feel fine for months after a flare. The problem isn’t just the myelin loss - it’s what happens after. When nerves are left without myelin for too long, they start to break down. Axons - the long, thread-like parts of nerve cells - begin to wither. And once an axon dies, it doesn’t grow back. Studies show that by the time someone has had MS for 10 to 15 years, about 40% of them have moved from relapsing-remitting to secondary progressive MS. That means the flares are fading, but the decline isn’t. They’re not getting new lesions on their MRI, but they’re still losing function. Why? Because the damage is no longer just surface-level. It’s deep inside the nerve fibers themselves.Why Inflammation Isn’t the Whole Story

For decades, doctors thought MS was mostly about immune attacks on the brain and spine. And yes - inflammation is a big part of the early disease. That’s why drugs like interferons and monoclonal antibodies help reduce relapses by 30 to 50%. They calm the immune system down. But here’s the problem: those drugs don’t stop progression. In fact, once someone enters the progressive phase - whether it’s secondary or primary - those same medications often do almost nothing. Why? Because the fire isn’t outside anymore. It’s inside. Research shows that in later stages, the immune cells that cause damage aren’t coming from the bloodstream. They’re living inside the brain, clustered in the meninges - the membranes covering the brain. These clusters act like tiny factories, pumping out chemicals that slowly poison the nerves. B cells, a type of immune cell, are now seen as major players in this process. And they’re not responding to the old anti-inflammatory drugs. Meanwhile, the nerves themselves are failing. Without myelin, they have to work harder to send signals. That means they burn through energy faster. Mitochondria - the power plants inside nerve cells - start to fail. Sodium channels, which help carry electrical signals, get damaged or disappear. The nerve can’t keep up. It starts to degenerate. And once it’s gone, it’s gone for good.The Silent Progression: Atrophy and Hidden Damage

You won’t see this on a regular MRI scan. But if you look closely - using special techniques like magnetization transfer ratio (MTR) - you’ll find that even areas of the brain that look normal are changing. The white matter, the gray matter, even the spinal cord are shrinking. This is called atrophy. A 2023 study tracked MS patients over six years and found that brain atrophy - especially in the gray matter - was the strongest predictor of long-term disability. Not the number of lesions. Not the frequency of relapses. The amount of tissue loss. Gray matter atrophy correlates with how well someone can do everyday tasks - walking, using their hands, thinking clearly. That’s why doctors now use tools like the Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite (MSFC) to measure disability, not just the old EDSS scale. EDSS looks at walking speed. MSFC looks at arm movement, leg strength, and thinking speed. And it’s more accurate. This is why someone can have a clean MRI but still be getting worse. The damage isn’t visible. It’s happening at the cellular level. Axons are dying. Neurons are shrinking. The brain is losing its ability to compensate.

What Do Current Treatments Actually Do?

There are 21 FDA-approved disease-modifying therapies for MS. All of them target inflammation. All of them reduce relapses. None of them stop the slow, steady loss of nerves. Drugs like ocrelizumab and cladribine work by wiping out certain immune cells. They’re powerful. They can cut relapse rates in half. But in progressive MS, their benefit is small - maybe a 10 to 15% delay in disability progression over two years. That’s not nothing. But it’s not a cure. Some newer drugs, like siponimod, are approved for secondary progressive MS. They work by trapping immune cells in lymph nodes so they can’t reach the brain. But again - they don’t repair nerves. They just slow the immune attack a little longer. The big gap? We still don’t have a drug that protects axons. That’s the holy grail.What’s on the Horizon? The Next Generation of MS Therapies

Scientists are now chasing three main strategies to stop neurological decline:- Neuroprotection: Drugs that shield nerves from damage. Some are targeting sodium channels to prevent nerve overwork. Others are trying to boost mitochondria function so nerves have more energy.

- Remyelination: Can we get the body to rebuild myelin? A few drugs in trials, like opicinumab and clemastine, are showing early signs of encouraging repair. But results are mixed.

- Stopping the inner brain inflammation: New drugs are being designed to target B cells inside the brain, not just in the blood. Some are even trying to block the toxic chemicals produced by immune clusters in the meninges.

What Can You Do Right Now?

While we wait for better drugs, there are things you can do to protect your nervous system:- Don’t smoke. Smoking doubles the risk of progression from relapsing to progressive MS.

- Get enough vitamin D. Low levels are linked to more lesions and faster decline. Aim for blood levels above 40 ng/mL.

- Exercise regularly. Aerobic activity, strength training, and balance work don’t just improve function - they may help protect nerves by increasing growth factors in the brain.

- Manage stress. Chronic stress raises inflammation. Mindfulness, yoga, and therapy can help.

- See your neurologist regularly. Track changes with MRI and functional tests. Early detection of atrophy means earlier action.

The Hard Truth

Multiple sclerosis isn’t one disease. It’s two. The first is the inflammatory phase - the one we can treat. The second is the neurodegenerative phase - the one we’re still learning to fight. The good news? We’re getting closer. We now know that axon loss is the main reason people with MS lose function over time. We know where the damage happens. We know which cells are involved. We’re not just guessing anymore. The bad news? We still don’t have a drug that stops it. But we’re not powerless. We can slow it. We can protect what’s left. And with new therapies on the horizon, the next decade might finally bring real hope for stopping the decline - not just the flares.Can disease-modifying therapies stop MS progression?

Current disease-modifying therapies reduce relapses by 30-50% in relapsing-remitting MS, but they have limited effect on long-term neurological decline. Most don’t stop axon loss or brain atrophy, which drive disability in progressive MS. Newer drugs like siponimod show modest slowing of progression in secondary progressive MS, but none reverse or halt neurodegeneration.

Why do I keep getting worse even when I don’t have relapses?

Because MS progression isn’t always caused by new inflammation. In later stages, damage happens inside the brain and spinal cord - nerves lose myelin, then slowly degenerate. Immune cells living in the meninges produce toxins that harm axons. This process doesn’t show up on standard MRIs, so you can decline without new lesions or flares.

Is brain atrophy a sign of worsening MS?

Yes. Brain and spinal cord atrophy - especially in gray matter - is one of the strongest predictors of long-term disability in MS. Studies show that people with faster atrophy rates are more likely to lose walking ability, hand function, and cognitive skills over time, even without new relapses.

Are there any drugs that protect nerves in MS?

Not yet. All currently approved MS drugs target inflammation. But over 17 clinical trials are now testing neuroprotective agents - including drugs that support mitochondria, block sodium channels, or promote remyelination. These are the most promising hope for stopping progression in the next 5-10 years.

Does exercise really help with MS progression?

Yes. Regular aerobic and strength training improves mobility, reduces fatigue, and may actually protect nerves. Exercise boosts brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein that supports neuron survival. Studies show people with MS who exercise regularly have slower brain atrophy and better functional outcomes than those who don’t.

What’s the difference between RRMS, SPMS, and PPMS?

RRMS (relapsing-remitting) involves clear flare-ups followed by recovery. SPMS (secondary progressive) starts after RRMS - flares fade, but disability slowly worsens. PPMS (primary progressive) has no initial relapses - decline is steady from the start. About 85% of people are diagnosed with RRMS first, and 40% of them transition to SPMS within 10-15 years.

Comments

lisa Bajram January 9, 2026 AT 22:27

Okay but let’s be real - if you’re not exercising, you’re basically letting your nerves starve. I’ve seen friends with MS go from walking with a cane to hiking trails just by doing yoga and swimming. It’s not magic, it’s biology. Your brain loves movement. BDNF doesn’t care about your diagnosis - it just wants you to move. And yeah, I cried the first time I could tie my shoes without help again. It’s not just physical - it’s soul-deep.

Paul Bear January 10, 2026 AT 07:26

Let’s not romanticize this. The paper cites a 2023 longitudinal study on gray matter atrophy as the primary predictor - which is correct - but the sample size was n=187, mostly RRMS patients under 50. Extrapolating to all MS phenotypes is statistically dubious. Also, ‘exercise boosts BDNF’ is a reductionist mantra. BDNF is not a miracle molecule; its receptor expression varies by genotype. You can’t just ‘move more’ and expect neuroprotection without addressing APOE4 status, comorbidities, or medication interactions. This is therapeutic nihilism dressed as empowerment.

Kunal Majumder January 11, 2026 AT 07:37

Man, I got diagnosed 5 years ago and thought I was done. Then I started biking 3 miles every morning. Not because I had to - because I wanted to feel alive again. Some days I’m slow, some days I’m shaky. But I show up. And that’s the win. You don’t need to be a athlete. You just need to not quit.

Jaqueline santos bau January 11, 2026 AT 13:26

So let me get this straight - you’re telling me the only reason I’m losing function is because I didn’t do enough yoga? And my neurologist is just lying to me when he says my meds are working? I’ve been on ocrelizumab for 3 years and I still can’t feel my toes. Are you seriously blaming me for my nerves dying? 🤡

Aurora Memo January 12, 2026 AT 14:33

I’ve been living with SPMS for 12 years. The hardest part isn’t the physical decline - it’s the loneliness. People see the cane and think ‘poor thing.’ But they don’t see the nights I cry because I can’t hug my granddaughter properly. I’m not here to cheerlead. I’m here to say: if you’re reading this, you’re not alone. And even if the drugs don’t fix everything, your presence - your voice - matters.

chandra tan January 14, 2026 AT 05:24

Back home in Kerala, we say ‘the body remembers what the mind forgets.’ My uncle had MS, never took fancy meds. Just turmeric milk, coconut oil massages, and daily walks by the sea. He lived to 82. I’m not saying ditch science - but don’t forget the old ways either. Sometimes the quietest remedies are the deepest.

Ian Cheung January 15, 2026 AT 03:34

Brain atrophy is the silent killer and nobody talks about it because it’s not flashy like lesions. But yeah - it’s the real enemy. I had a scan last month. My gray matter volume dropped 2.3% in 10 months. No new lesions. Just… disappearing. They call it ‘progressive’ like it’s a phase. It’s not. It’s erosion. And we’re running out of time to stop it.

Dwayne Dickson January 15, 2026 AT 21:23

Oh wow. Another ‘exercise is medicine’ sermon. Because clearly, if I just did more Pilates, my axons would magically regrow. Let me get this straight - you’re recommending yoga to someone whose spinal cord is actively degenerating? How about we start by acknowledging that we’re losing this war? And that your ‘hopeful’ advice sounds like toxic positivity wrapped in a TED Talk?

Ted Conerly January 17, 2026 AT 20:14

Hey - I’m not a doctor, but I’ve been on cladribine for 2 years. My relapses are gone. But my balance? Still trash. My hands? Still numb. I don’t need another lecture on BDNF. I need a drug that doesn’t just suppress my immune system - but actually rebuilds what’s broken. Until then, I’m holding on. And I’m not giving up. Not today.

Faith Edwards January 19, 2026 AT 18:49

It’s frankly irresponsible to suggest that vitamin D and yoga are viable alternatives to neuroprotection. This is not a wellness blog. This is a neurological catastrophe. The fact that you’re promoting lifestyle hacks as if they’re equivalent to clinical intervention reveals a profound misunderstanding of disease biology. You’re not helping. You’re distracting.

Jay Amparo January 20, 2026 AT 07:07

My sister had PPMS. She didn’t have relapses. Just… fading. One day she could hold a pen. Next, she couldn’t button her shirt. We didn’t know it was happening until it was too late. I wish someone had told us earlier about atrophy. Not to scare us - just to prepare us. Knowledge isn’t power here. It’s peace. And I’m grateful for this post. It’s the first time I felt seen.

Lisa Cozad January 21, 2026 AT 07:01

I’m a nurse in a neuro clinic. I see this every week. People think clean MRIs mean they’re fine. They’re not. The real story is in the walking speed test, the 9-hole peg test, the word recall. We measure function - not lesions. If you’re not tracking your functional decline, you’re flying blind. Please ask your neurologist for an MSFC. It’s not optional. It’s essential.

Saumya Roy Chaudhuri January 23, 2026 AT 03:27

Everyone’s talking about BDNF and mitochondria like they’re the answer - but did you read the phase 2 trial data for opicinumab? 78% failure rate. Clemastine? No clinically meaningful remyelination. And siponimod? Only delays progression by 21 weeks over two years. We’re not on the brink of a breakthrough. We’re on the brink of another decade of false hope. Stop pretending we’re close. We’re not.

anthony martinez January 23, 2026 AT 15:28

So the takeaway is: we have 21 drugs that all do the same thing, and none of them fix the real problem? And the only thing that might help is something we can’t even measure reliably? Great. So we’re just supposed to sit here and wait for science to catch up while our bodies turn to dust? Thanks for the update, I guess.

Ritwik Bose January 24, 2026 AT 17:35

Thank you for writing this. 🙏 I’m from India - where MS is still misunderstood. Many think it’s ‘stress’ or ‘bad karma.’ Your post is the first thing I’ve seen that explains it without sugarcoating. I shared it with my family. They finally get it. I’m not broken. I’m fighting a war no one sees. And now… they see it too.