When a drug first hits the market, the company that made it gets a patent that lasts about 20 years. That’s supposed to give them time to recoup their research costs before anyone else can copy it. But in reality, many blockbuster drugs stay protected for decades - not because of that original patent, but because of a whole stack of secondary patents. These aren’t about the active ingredient. They’re about everything else: how it’s made, how it’s taken, even what disease it treats. And together, they form what experts call a patent thicket - a legal maze designed to keep generics out long after the original patent expires.

What Exactly Are Secondary Patents?

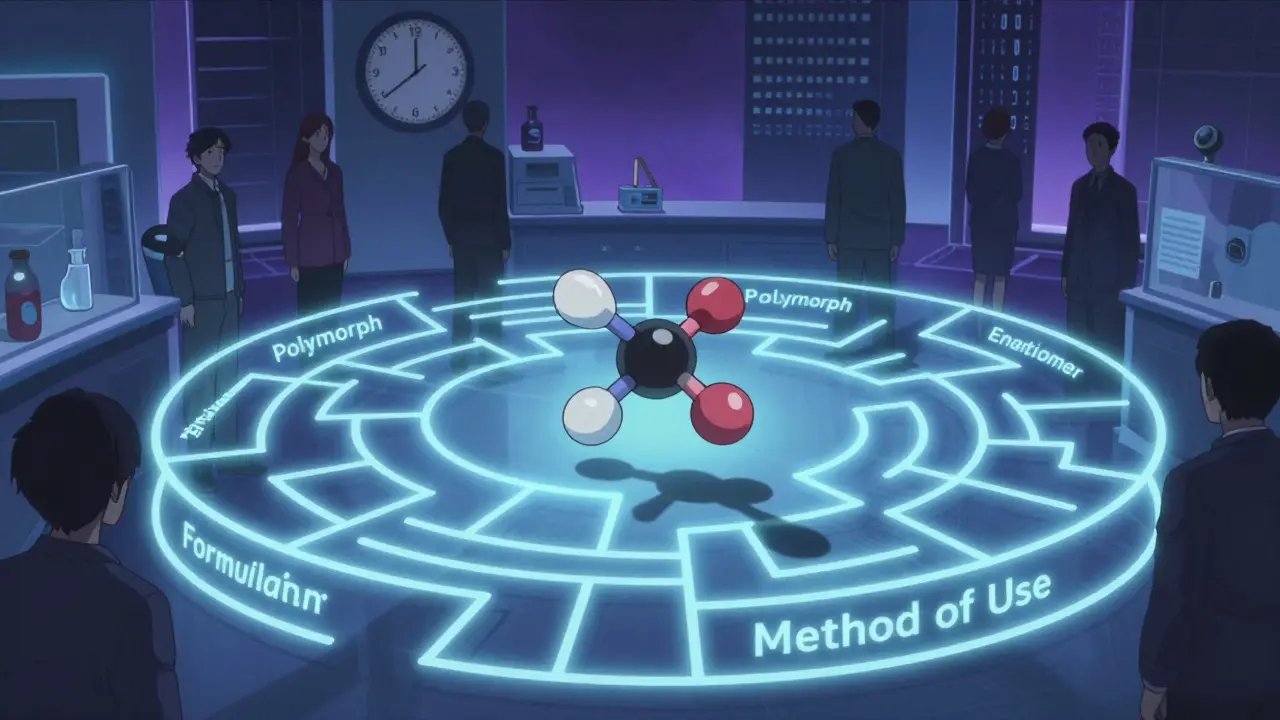

Think of a drug like a car. The primary patent is the engine - the actual chemical compound that makes it work. Secondary patents? They’re the tires, the GPS, the heated seats. They protect things like:

- Formulations: A pill that releases medicine slowly over 12 hours instead of 4.

- Polymorphs: Different crystal shapes of the same molecule - one might be more stable or easier to absorb.

- Enantiomers: Switching from a mix of two mirror-image molecules to just one that works better (like Nexium from Prilosec).

- Method of use: Patenting a new condition the drug treats - even if the drug itself is old.

- Combinations: Pairing an old drug with another drug in one pill.

These aren’t just technical tweaks. They’re strategic moves. A company doesn’t wait until the primary patent is about to expire to file these. They start building their thicket 5 to 7 years ahead. By the time the original patent runs out, there are already 10, 20, even 100+ secondary patents in place - each one a potential roadblock for generic manufacturers.

How They Delay Generic Drugs

The U.S. FDA keeps a public list called the Orange Book that includes patents linked to brand-name drugs. But here’s the catch: only certain types of secondary patents - mainly formulation and method-of-use patents - can be listed. Others are kept quiet, like hidden traps. Generic companies have to dig through all of them before they can even try to sell a copy.

When a generic maker files for approval, they must certify that they’re not infringing on any listed patents. If they say no, the brand-name company can sue. That lawsuit automatically blocks the generic from entering the market for 30 months - even if the court later rules the patent is invalid. This delay gives the brand time to switch patients to a new version of the drug, often with a slightly different formulation. It’s called product hopping.

Take Humira. Its primary patent expired in 2016. But AbbVie had filed 264 secondary patents. The result? No generic version entered the U.S. market until 2023. During that time, Humira brought in over $20 billion a year. Generic alternatives could have cut those costs by 80%.

Who Benefits? Who Pays?

The pharmaceutical industry says secondary patents drive innovation. They point to real improvements: easier dosing, fewer side effects, new uses for old drugs. For example, a new formulation of a chemotherapy drug reduced severe nausea by 37% in trials. That’s meaningful.

But the data shows most secondary patents aren’t about that. A 2016 Harvard study found only 12% of secondary patents represented clinically meaningful improvements. The rest? Minor changes - like switching from a tablet to a liquid - that don’t change how well the drug works, just how much it costs.

Patients and insurers pay the price. Pharmacy benefit managers report that secondary patents raise drug spending by about 8.3% each year. Generic manufacturers say navigating these patent thickets adds $15-20 million in legal costs per product and delays entry by over 3 years. That’s why generic companies file Paragraph IV certifications against 92% of listed secondary patents - but only win about 38% of the time.

Global Differences: Where It Works - and Where It Doesn’t

The U.S. is the most permissive. The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 created the system that lets companies stack patents like this. But other countries don’t play by the same rules.

India’s patent law, since 2005, blocks patents on new forms of known drugs unless they show “enhanced efficacy.” That’s why Novartis couldn’t patent a new crystal form of Gleevec - the court said it was just a tweak, not a breakthrough. As a result, generics entered India years before the U.S.

Brazil requires approval from its health ministry before a patent can be enforced. The European Union demands proof of “significant clinical benefit” for some secondary patents. These rules keep drug prices lower. In places like India, generic versions of drugs like Humira and Sovaldi became available years before they hit the U.S. market.

The Future: Crackdowns and Changes

Pressure is building. The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act in the U.S. lets Medicare challenge certain secondary patents. The European Commission’s 2023 Pharmaceutical Strategy calls out patent thickets as barriers to access. The WHO says secondary patents are the main reason 68 low- and middle-income countries can’t get affordable versions of essential medicines.

Some legal shifts are already happening. In 2023, a federal court narrowed the scope of antibody patents in the Amgen v. Sanofi case - a sign courts might start demanding more proof of invention. Experts predict that by 2027, companies will need to show real clinical value to get secondary patents approved. Otherwise, regulators and courts may start seeing them as legal tricks, not innovation.

For now, the system still works - for big pharma. The top 10 drug companies hold 73% of all secondary patents. Pfizer alone has over 14,200 active ones. But the tide is turning. As more countries tighten rules and courts demand higher standards, the days of endless patent stacking may be numbered. The real question isn’t whether secondary patents exist - it’s whether they’ll continue to be used to delay access, or if they’ll finally be held to the same standard as true innovation.

Are secondary patents legal?

Yes, secondary patents are legal in the U.S. and many other countries. They’re protected under patent law as long as they meet basic criteria like novelty and non-obviousness. But their legitimacy is heavily debated. Courts and regulators are increasingly questioning whether minor changes - like a new tablet coating or a slightly different dose - truly deserve patent protection. Some countries, like India and Brazil, have laws that explicitly limit or block them.

How long do secondary patents last?

Secondary patents last 20 years from the date they’re filed - same as primary patents. But because they’re often filed years after the original patent, they can add 4 to 11 extra years of exclusivity after the main patent expires. For example, a drug with a primary patent expiring in 2020 might still be protected by a secondary patent filed in 2015, which won’t expire until 2035.

Can generics challenge secondary patents?

Yes, generic manufacturers routinely challenge secondary patents through legal filings called Paragraph IV certifications. These are formal notices that a generic company plans to enter the market and believes the patent is invalid or not infringed. About 92% of listed secondary patents face these challenges. But only about 38% of those challenges succeed in court, largely because the legal process is expensive and slow - and brand companies often settle with generics to delay competition.

Why do companies file so many secondary patents?

It’s about revenue. A single blockbuster drug can earn over $1 billion a year. Extending exclusivity by even two years means billions more in profit. Companies invest heavily in patenting because the payoff is huge. Studies show that for every additional billion in annual sales, a company’s chance of filing a secondary patent increases by 17%. For drugs like Humira, Enbrel, or Humalog, the financial incentive to delay generics is enormous.

Do secondary patents improve patient care?

Sometimes, yes. A few secondary patents have led to real improvements - like a gentler formulation that reduces side effects or a new use for an old drug that helps treat rare diseases. But most don’t. A Harvard study found only 12% of secondary patents led to meaningful clinical benefits. Many are minor changes that don’t improve how well the drug works - just how much it costs. Patients often end up paying more for a version of the same drug with no real advantage.

Comments

Chima Ifeanyi February 8, 2026 AT 08:50

Let’s cut through the noise: secondary patents aren’t innovation-they’re regulatory arbitrage. The system is engineered to maximize shareholder value, not patient access. The 12% clinically meaningful stat? That’s the tip of the iceberg. The rest are patent thickets built on trivial modifications: pH tweaks, coating thickness, delayed-release profiles that don’t alter pharmacokinetics meaningfully. This isn’t capitalism-it’s rent-seeking dressed up as IP protection. And the FDA’s Orange Book? A rubber stamp for pharma’s legal warfare machine. The real scandal? No one’s holding them accountable for stacking 264 patents on Humira. That’s not a business model-it’s a cartel.

Tori Thenazi February 9, 2026 AT 11:00

Okay, but… have you ever thought… maybe… the government is in on it?? Like, the FDA, the courts, Big Pharma-they’re all connected through this shadow network of revolving doors!! I read this one blog post where a former FDA commissioner went straight to work for Pfizer… and then, like, 3 months later, a patent was approved for a drug that was basically the same as the old one?? And don’t get me started on the secret meetings at the WHO!! I mean, why else would India be allowed to make generics but we can’t?? It’s all a setup!! We’re being played!!

Angie Datuin February 10, 2026 AT 02:27

I’ve worked in pharmacy for 18 years, and I’ve seen patients struggle with the cost of these drugs every day. I don’t judge the companies-I get that R&D is expensive. But when a patient has to choose between insulin and rent, and the only reason they can’t get a cheaper version is because of a patent on the flavoring… that’s not innovation. That’s just… sad.

Jonah Mann February 11, 2026 AT 11:10

Man, I read this whole thing and I’m like… wow. So like, the primary patent is the engine, right? And then the secondary ones are like… the spoiler, the tinted windows, the fancy rims? Like, sure, it looks nice, but does it go faster? Nah. And then they sue you if you try to make a copy with regular rims? That’s wild. I mean, if I built a car with the same engine but different seats, I wouldn’t get sued. But for drugs? It’s a whole legal nightmare. And why do we even let this happen??

Brandon Osborne February 11, 2026 AT 13:33

THIS IS WHY AMERICA IS BROKE!! PEOPLE ARE DYING BECAUSE OF THESE CORRUPT PHARMA BARONS WHO ARE STUFFING THEIR POCKETS WHILE KIDS GO WITHOUT MEDICINE!! I SAW A VIDEO ON TIKTOK OF A WOMAN WHO HAD TO SELL HER CAR TO PAY FOR HER DAD’S MEDS-AND IT WAS ALL BECAUSE OF THESE STUPID SECONDARY PATENTS!! THEY’RE NOT INNOVATING-THEY’RE ROBBING US!! WE NEED TO BURN DOWN THE FDA AND START OVER!!

Lyle Whyatt February 12, 2026 AT 11:51

It’s fascinating, really, how the patent system evolved into this intricate ecosystem of legal maneuvering. The original intent of patent law-to incentivize innovation through temporary monopolies-has been so thoroughly co-opted by corporate strategy that we’re now witnessing a phenomenon where the very mechanism designed to promote progress becomes its greatest impediment. Take the case of polymorphs: the crystalline structure of a molecule can indeed affect bioavailability, but when companies file patents on every minor variation-every polymorphic form, every solvate, every salt derivative-it becomes less about science and more about litigation strategy. And when you layer on method-of-use patents for conditions the drug was never originally intended to treat, you get a system where innovation is measured not in clinical outcomes but in legal filings. The result? A generation of patients who are priced out, and a healthcare system that’s drowning in administrative overhead.

Ken Cooper February 13, 2026 AT 01:06

So like… wait, so if a company makes a drug that’s been around for 10 years, and then they just change the pill from red to blue and say ‘oh this is better for absorption’… they can get a whole new 20-year patent?? That’s insane. And then they sue generics for doing the same thing? I mean, I get that R&D costs money, but if the only thing that changed is the color of the pill… shouldn’t that just be a trademark?? Not a patent?? And why does the FDA even let them list that stuff?? I feel like I’m missing something here…

MANI V February 14, 2026 AT 03:00

India has always been the true champion of the people. While the U.S. and Europe let pharma giants strangle access with patent thickets, India’s courts have stood firm. Novartis tried to patent Gleevec’s new crystal form-India said no. Why? Because it’s not innovation, it’s exploitation. And now, thanks to Indian generics, millions of patients across Africa and Southeast Asia are alive today. Meanwhile, Americans pay $10,000 a year for drugs that cost $200 to make. The West has lost its moral compass. India didn’t just break the system-it exposed it.

Jessica Klaar February 14, 2026 AT 10:05

As someone who’s worked in global health policy, I’ve seen firsthand how secondary patents lock out low-income countries. The WHO report saying 68 countries can’t access essential medicines? That’s not a statistic-it’s a humanitarian crisis. And the sad part? The solutions already exist: compulsory licensing, patent pools, tiered pricing. But they’re ignored because the profit margins are too high. We need to stop pretending this is about science. It’s about power. And if we don’t act now, we’re going to keep watching people die because a corporation didn’t want to share.

glenn mendoza February 16, 2026 AT 02:29

While the economic implications of patent thickets are significant, it is imperative that we recognize the broader ethical and societal consequences of prolonging market exclusivity through non-clinically significant modifications. The current framework incentivizes legal stratagems over therapeutic advancement, thereby undermining the foundational purpose of pharmaceutical innovation: to improve human health. Regulatory reform must prioritize substantive clinical benefit over procedural novelty. Otherwise, we risk institutionalizing a system that commodifies medicine rather than democratizing it.

Patrick Jarillon February 17, 2026 AT 14:58

Oh, so now it’s ‘patent thicket’? That’s just code for ‘we’re scared of competition’. The whole system is rigged. The U.S. government gave Big Pharma this monopoly, then turned a blind eye while they stacked patents like Jenga blocks. And now you’re surprised generics can’t get in? Newsflash: the patents aren’t valid. They’re just… legally convenient. And the courts? They’re owned. I bet you didn’t know that 89% of patent lawsuits are settled before trial-because the generics can’t afford to fight. This isn’t capitalism. This is feudalism with lawyers.

Randy Harkins February 17, 2026 AT 20:49

Wow, this was so well written 😊 I didn’t even realize how much this affected everyday people. I always thought patents were just about protecting new inventions, but now I see it’s more like… a game. And the players are all big companies. I’m gonna share this with my mom-she’s on 3 different meds and can’t afford the generics. Thanks for putting this out there 💙

Camille Hall February 19, 2026 AT 11:41

It’s wild how the same companies that preach innovation are the ones blocking access. I work with community clinics, and we see patients skipping doses because they can’t afford the branded version-even when the generic is chemically identical. The emotional toll is real. People feel like they’re being punished for being poor. And yet, we’re told this system is ‘fair’. It’s not. It’s just profitable.

Ritteka Goyal February 21, 2026 AT 01:33

Bro India is the real hero here!! While US and EU are busy patenting every damn thing under the sun, India is making life-saving drugs affordable for millions!! And guess what? The WHO says 80% of global generics come from India!! So yeah, let’s talk about how the West is trying to kill innovation by hoarding patents!! Meanwhile, India is saving lives!! 🇮🇳💪

Chelsea Deflyss February 22, 2026 AT 19:24

So… wait… so if a company just changes the pill size? That’s a patent? That’s not even a real change… like… what even is the point??